Note: the information in this article is either publicly available or my own opinion.

Look at your phone. Now imagine a computer that is eighty times slower and about the same multiple bigger. I know what you are thinking: that is one obsolete piece of computing. On May 11th, 1997, that antiquity captured the world’s imagination. IBM’s Deep Blue beat world champion Gary Kasparov at chess. For the first time, computer programming beat human intelligence. And it only went downhill from there. The machines became exponential better. They beat us at increasingly difficult games like Jeopardy (IBM again with Watson) and Go (Google Deep Mind). They even pass bar exams. As I went through my presentation at the first ever online Creacion Forum, the anxiety about A.I. bubbled up to the surface with questions from the audience. Some of them barely got started in their careers and they were nervous: A.I. was coming for them.

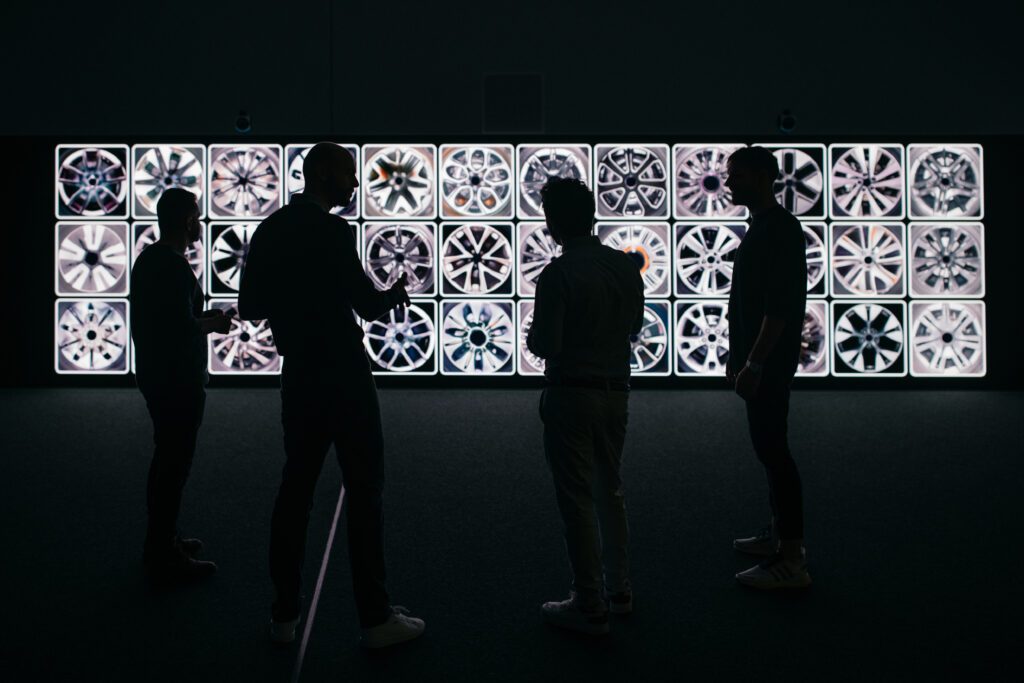

A few years ago, computer made patterns were the rage all over my LinkedIn feed. Today it is Dall-E, Mid-Journey, or Chat GPT. Trends come and go but A.I. is something different. Siri landed on your phone a dozen years ago. It is sweeping all fields of human endeavours, everything everywhere all at once, just like the movie. Automotive design is one of its targets. Audi was the first to use A.I. in a design studio context to generate rim ideas with FelGAN. Other A.I. examples include generative design and machine learning. Both disciplines will play a key role in electric vehicles, with definitions given by Wikipedia:

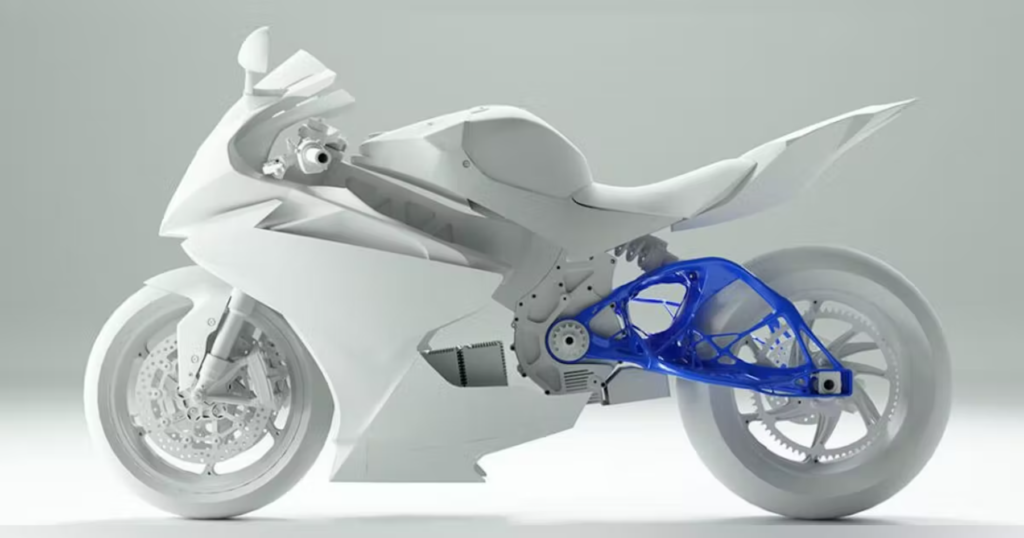

Generative design is an iterative design process that generates outputs that meet specified constraints to varying degrees. In a second phase, designers can then provide feedback to the generator that explores the feasible region by selecting preferred outputs or changing input parameters for future iterations. Either or both phases can be done by humans or software. You can optimize weight and materials costs with this method.

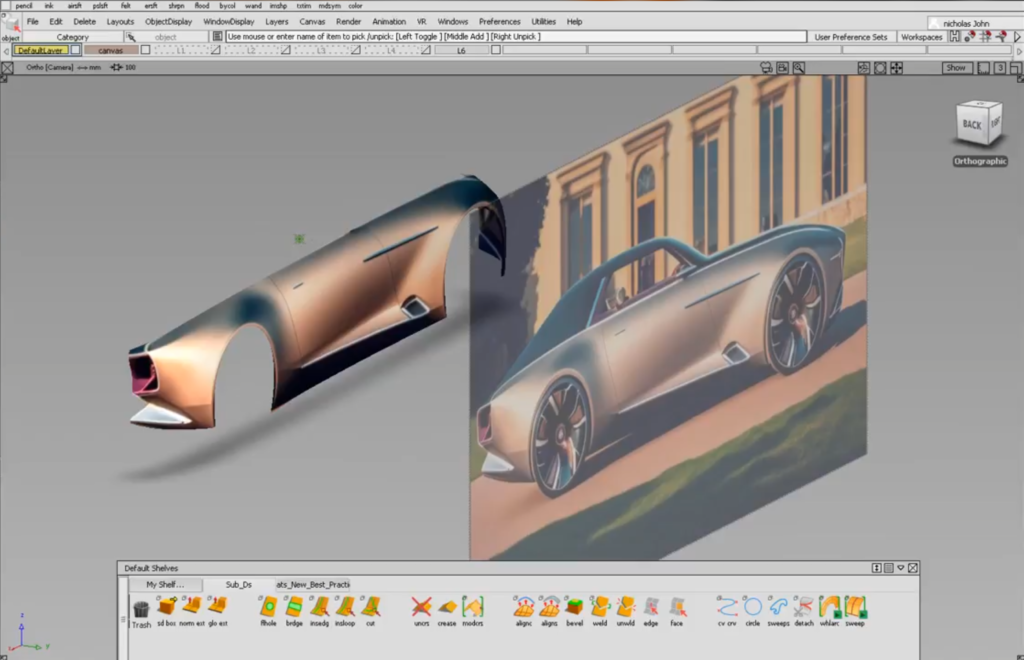

Machine learning algorithms build a model based on sample data, known as training data, to make predictions or decisions without being explicitly programmed to do so. Machines can learn how to make the most aerodynamic shape using this method. After thinking about it, here is my idea (for free, you’re welcome). Feed A.I. a clay scan and a matching 3D Alias model. After a while, it might learn how to build a model without human input and turn it around in minutes.

Where is all this leading to? A.I. is a huge weapon but like any weapon, it needs to be calibrated and aimed properly. In meetings with students this year, they already generate sketch alternatives with A.I. It is out of the box; you might as well embrace it. Much like today, the use of technology will be on a sliding scale. A design director like Matt Swann can use accessible A.I. like Midjourney with spectacular results.

As you get more technical, people will use it to write scripts, to produce patterns or to automate tasks. As demonstrated by Nick John, modellers will be able to extract basic 3D math from the A.I. sketches to start their 3D models. As we get more technical other users will optimize weight or aerodynamics. If you want to accelerate design cycles, those activities will need to be concurrent to or integrated with design. I predict a new form of I.T. will be in place within the studio to support all those creative activities. For those young people worried about their jobs, it might generate careers for them that are not even being thought of today. Ten years ago, nobody heard of a “parametric modeller”.

To go back to the chess analogy, there are now championships that allow the use of computers. Computers crunch the possibilities while humans direct strategy: that is the key. You calibrate and aim. The choices and the possibilities are endless. That might lead us to a vastly different conundrum: what if there is too much choice?